Glass Manufacturing Process - Soda Lime

Glass is a rigid, brittle, and hard under cooled Amorphous substance and posses high viscosity to reduce crystallization physically; It is usually transparent, opaque and sometime translucent.

Chemically Glass is a fused mixture of silicate and alkaline or alkaline earth metals and other glass constituents that such as CaO from limestone (CaCO3), Na2O from Soda Ash(Na2CO3), Al2O3 from Feldsper etc.

Glass production involves two main methods – the float glass process that is used to produce sheet glass like window sheet, and glassblowing that produces bottles and other containers; Both follow

The glass –

float glass as we know - is manufactured by the PPG process. This process was

invented by Sir Alistair Pilkington in 1952 and is the most popular and widely

used process in manufacturing architectural glass in the world today.

It consists

of the following steps:

Glass Sheet Making with float method

Stage 1-

Melting & Refining:

Fine grained

ingredients closely controlled for quality, are mixed to make a batch, which

flows into the furnace, which is heated up to 1500 degree Celsius.

The raw

materials that go into the manufacturing of clear float glass are:

- SiO2 – Silica Sand (Former)

- Na2O – Sodium Oxide from Soda

Ash (Fluxing agent)

- CaO – Calcium oxide from

Limestone

- MgO – Dolomite

- Al2O3 – Feldspar

The above

raw materials primarily mixed in batch helps to make clear glass. If certain

metal oxides like are mixed to this batch they impart colors to the glass giving it

a body tint.

Examples of such metal oxide are:

- NiO & CoO – to give grey

tinted glasses (Oxides of Nickel & Cobalt)

- SeO – to give Bronze tinted

glasses (oxide of Selenium) Some time used to mask ion (III) in flint glass making.

- Fe2O3 – To give Green tinted

glasses (oxides of iron which at times is also present as impurity in

Silica Sand which is the main former of glass)

- CoO – To give blue tinted glass

(oxides of Cobalt)

Apart from

the above basic raw material, broken glass (cullet), is added to the mixture

to the tune of nearly 25% ~ 30% which acts primarily as flux. The flux in a

batch helps in reducing the melting point of the batch thus reducing the energy

consumed to carry out the process.

Glass from

the furnace gently flows over the refractory spout on to the mirror-like

surface of molten tin, starting at 1100 deg Celsius and leaving the float bath

as solid ribbon at 600 deg Celsius.

Stage 3 -

Coating (for making reflective glasses):

Coatings

that make profound changes in optical properties can be applied by advanced

high temperature technology to the cooling ribbon of glass. Online Chemical Vapour

Deposition (CVD) is the most significant advance in the float process since it

was invented. CVD can be used to lay down a variety of coatings, a few microns

thick, for reflect visible and infra-red radiance for instance. Multiple

coatings can be deposited in the few seconds available as the glass flows

beneath the coater (e.g. Sunergy)

Stage 4 -

Annealing:

Despite the

tranquillity with which the glass is formed, considerable stresses are

developed in the ribbon as the glass cools. The glass is made to move through

the annealing lehr where such internal stresses are removed, as the glass is

cooled gradually, to make the glass more prone to cutting.

Stage 5 -

Inspection:

To ensure

the highest quality inspection takes place at every stage. Occasionally a bubble

that is not removed during refining, a sand grain that refuses to melt or a

tremor in the tin puts ripples in the glass ribbon. Automated online inspection

does two things. It reveals process faults upstream that can be corrected. And

it enables computers downstream to steer round the flaws. Inspection technology

now allows 100 million inspections per second to be made across the ribbon,

locating flaws the unaided eye would be unable to see.

Stage 6 -

Cutting to Order:

Diamond

steels trim off selvedge – stressed edges- and cut ribbon to size dictated by

the computer. Glass is finally sold only in square meters.

Blow and Blow Method for Glass container(Hollow Glass) Making.

Broadly,

modern glass container factories are three-part operations: the batch house,

the hot end, and the cold end. The batch house handles the raw materials; the

hotend handles the manufacture proper—the forehearth, annealing Lehrs, and

forming machines made up of individual sections(IS.); and the cold end handles the product-inspection and packaging.

Hot end

The

following table lists common viscosity fixpoints, applicable to large-scale

glass production experimental results.

| log10(η, Pa·s) | log10(η, P) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Melting Point (glass melt homogenization and fining) |

| 3 | 4 | Working Point (pressing, blowing, gob forming) |

| 4 | 5 | Flow Point |

| 6.6 | 7.6 | Littleton Softening Point (Glass deforms visibly under its own weight. Standard procedures ASTM C338, ISO 7884-3) |

| 8–10 | 9–11 | Dilatometric Softening Point, Td, depending on load[2] |

| 10.5 | 11.5 | Deformation Point (Glass deforms under its own weight on the μm-scale within a few hours.) |

| 11–12.3 | 12–13.3 | Glass Transition Temperature, Tg |

| 12 | 13 | Annealing Point (Stress is relieved within several minutes.) |

| 13.5 | 14.5 | Strain Point (Stress is relieved within several hours.) |

Batch

processing system (batch house)

Batch

processing is one of the initial steps of the glass-making process. The batch

house simply houses the raw materials in large silos (fed by truck or railcar)

and holds anywhere from 1–5 days of material. Some batch systems include

material processing such as raw material screening/sieve, drying, or

pre-heating (i.e. cullet). Whether automated or manual, the batch house

measures, assembles, mixes, and delivers the glass raw material recipe (batch)

via an array of chutes, conveyors, and scales to the furnace. The batch enters

the furnace at the 'dog house' or 'batch charger'. Different glass types,

colors, desired quality, raw material purity / availability, and furnace design

will affect the batch recipe.

Furnace

The hot end of a glassworks is where the molten glass is formed into glass products, beginning when the batch is fed into the furnace at a slow, controlled rate by the batch processing system (batch house). The furnaces are natural gas- or fuel oil-fired, and operate at temperatures up to 1,575 °C (2,867 °F).[3] The temperature is limited only by the quality of the furnace’s superstructure material and by the glass composition. Types of furnaces used in container glass making include 'end-port' (end-fired), 'side-port', and 'oxy-fuel'. Typically, furnace "size" is classified by metric tons per day (MTPD) production capability.

Forming process[edit]

This section may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please help improve it to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. (April 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

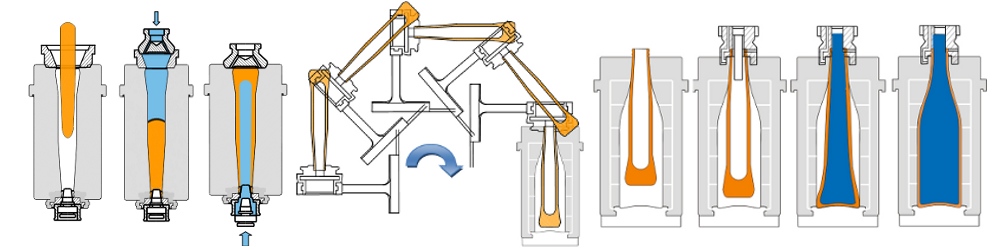

There are currently two primary methods of making glass containers: the blow & blow method for narrow-neck containers only, and the press & blow method used for jars and tapered narrow-neck containers .

Figure 1: Steps during Blow&Blow container forming process

In both methods, a stream of molten glass, at its plastic temperature (1,050–1,200 °C [1,920–2,190 °F]), is cut with a shearing blade to form a solid cylinder of glass, called a gob. The gob is of predetermined weight just sufficient to make a bottle. Both processes start with the gob falling, by gravity, and guided, through troughs and chutes, into the blank moulds, two halves of which are clamped shut and then sealed by the "baffle" from above.

In the blow and blow process,[4] the glass is first blown through a valve in the baffle, forcing it down into the three-piece "ring mould" which is held in the "neckring arm" below the blanks, to form the "finish", [The term "finish" describes the details (such as cap sealing surface, screw threads, retaining rib for a tamper-proof cap, etc.) at the open end of the container.] The compressed air is blown through the glass, which results in hollow and partly formed container. Compressed air is then blown again at the second stage to give final shape.

Containers are made in two major stages. The first stage moulds all the details ("finish") around the opening, but the body of the container is initially made much smaller than its final size. These partly manufactured containers are called parisons, and quite quickly, they are blow-molded into final shape.

Referring to the mechanism, the "rings" are sealed from below by a short plunger. After the "settleblow" finishes, the plunger retracts slightly, to allow the skin that's formed to soften. "Counterblow" air then comes up through the plunger, to create the parison. The baffle rises and the blanks open. The parison is inverted in an arc to the "mould side" by the "neckring arm", which holds the parison by the "finish".

As the neckring arm reaches the end of its arc, two mould halves close around the parison. The neckring arm opens slightly to release its grip on the "finish", then reverts to the blank side. Final blow, applied through the "blowhead", blows the glass out, expanding into the mould, to make the final container shape.

In the press and blow process,[4] the parison is formed by a long metal plunger which rises up and presses the glass out, in order to fill the ring and blank moulds.[5] The process then continues as before, with the parison being transferred to the final-shape mould, and the glass being blown out into the mould.

The container is then picked up from the mould by the "take-out" mechanism, and held over the "deadplate", where air cooling helps cool down the still-soft glass. Finally, the bottles are swept onto a conveyor by the "push out paddles" that have air pockets to keep the bottles standing after landing on the "deadplate"; they're now ready for annealing.

Forming machines[edit]

The forming machines hold and move the parts that form the container. The machine consist of basic 19 mechanisms in operation to form a bottle and generally powered by compressed air (high pressure - 3.2 bar and low pressure - 2.8 bar), the mechanisms are electronically timed to coordinate all movements of the mechanisms. The most widely used forming machine arrangement is the individual section machine (or IS machine). This machine has a bank of 5–20 identical sections, each of which contains one complete set of mechanisms to make containers. The sections are in a row, and the gobs feed into each section via a moving chute, called the gob distributor. Sections make either one, two, three or four containers simultaneously. (Referred to as single, double, triple and quad gob). In the case of multiple gobs, the shears cut the gobssimultaneously, and they fall into the blank moulds in parallel.

Internal treatment

After the forming process, some containers—particularly those intended for alcoholic spirits—undergo a treatment to improve the chemical resistance of the inside, called internal treatment or dealkalization. This is usually accomplished through the injection of a sulfur- or fluorine-containing gas mixture into bottles at high temperatures. The gas is typically delivered to the container either in the air used in the forming process (that is, during the final blow of the container), or through a nozzle directing a stream of the gas into the mouth of the bottle after forming. The treatment renders the container more resistant to alkali extraction, which can cause increases in product pH, and in some cases container degradation.

Annealing[edit]

As glass cools, it shrinks and solidifies. Uneven cooling causes weak glass due to stress. Even cooling is achieved by annealing. An annealing oven (known in the industry as a Lehr) heats the container to about 580 °C (1,076 °F), then cools it, depending on the glass thickness, over a 20 – 60 minute period.

Cold end[edit]

The role of the cold end is to spray on a polyethylene coating for abrasion resistance and increased lubricity, inspect the containers for defects, package the containers for shipment, and label the containers.

Inspection equipment[edit]

Glass containers are 100% inspected; automatic machines, or sometimes persons, inspect every container for a variety of faults. Typical faults include small cracks in the glass called checks and foreign inclusions called stones which are pieces of the refractory brick lining of the melting furnace that break off and fall into the pool of molten glass, or more commonly oversized silica granules (sand) that have failed to melt and which subsequently are included in the final product. These are especially important to select out due to the fact that they can impart a destructive element to the final glass product. For example, since these materials can withstand large amounts of thermal energy, they can cause the glass product to sustain thermal shock resulting in explosive destruction when heated. Other defects include bubbles in the glass called blisters and excessively thin walls. Another defect common in glass manufacturing is referred to as a tear. In the press and blow forming, if a plunger and mould are out of alignment, or heated to an incorrect temperature, the glass will stick to either item and become torn. In addition to rejecting faulty containers, inspection equipment gathers statistical information and relays it to the forming machine operators in the hot end. Computer systems collect fault information and trace it to the mould that produced the container. This is done by reading the mould number on the container, which is encoded (as a numeral, or a binary code of dots) on the container by the mould that made it. Operators carry out a range of checks manually on samples of containers, usually visual and dimensional checks.

Secondary processing[edit]

Sometimes container factories will offer services such as labelling. Several labelling technologies are available. Unique to glass is the Applied Ceramic Labelling process (ACL). This is screen-printing of the decoration onto the container with a vitreous enamel paint, which is then baked on. An example of this is the original Coca-Cola bottle. Absolut Vodka Bottles have various added services such as: Etching (Absolut Citron/) Coating (Absolut Raspberry/Ruby Red) and Applied Ceramic Labelling (Absolut Blue/Pears/Red/Black).

Packaging[edit]

Glass containers are packaged in various ways. Popular in Europe are bulk pallets with between 1000 and 4000 containers each. This is carried out by automatic machines (palletisers) which arrange and stack containers separated by layer sheets. Other possibilities include boxes and even hand-sewn sacks. Once packed, the new "stock units" are labelled and warehoused.

Coatings[edit]

Glass containers typically receive two surface coatings, one at the hot end, just before annealing and one at the cold end just after annealing. At the hot end a very thin layer of tin(IV) oxide is applied either using a safe organic compound or inorganic stannic chloride. Tin based systems are not the only ones used, although the most popular. Titanium tetrachloride or organo titanates can also be used. In all cases the coating renders the surface of the glass more adhesive to the cold end coating. At the cold end a layer of typically, polyethylene wax, is applied via a water based emulsion. This makes the glass slippery, protecting it from scratching and stopping containers from sticking together when they are moved on a conveyor. The resultant invisible combined coating gives a virtually unscratchable surface to the glass. Due to reduction of in-service surface damage, the coatings often are described as strengtheners, however a more correct definition might be strength-retaining coatings.

Ancillary processes – compressors and cooling[edit]

Forming machines are largely powered by compressed air and a typical glass works will have several large compressors (totaling 30k–60k cfm) to provide the needed compressed air. Furnaces, compressors and forming machine generate quantities of waste heat which is generally cooled by water. Hot glass which is not used in the forming machine is diverted and this diverted glass (called cullet) is generally cooled by water, and sometimes even processed and crushed in a water bath arrangement. Often cooling requirements are shared over banks of cooling towers arranged to allow for backup during maintenance.

Thanks for this. I really like what you've posted here and wish you the best of luck with this blog and thanks for sharing. Virtual Administrative Assistant

ReplyDelete